There's a bit of a Putney vibe going on at the moment as the Putney Pest House plaque wasn't the only interesting result of my recent stroll around the Common. For a start my eye was caught by this smart metal plate attached to a paving slab.

I think I must have been aware of these plates because it certainly didn't strike me as being particularly out of the ordinary, even though I couldn't recall exactly when or where I might have come across them before. I suspect it might have been one of those things that were reasonably common in the past but which are now far rarer thanks to frequent removal and repair of paving slabs.This example was on the side of someone's cross-over drive and you can get a better idea of the scale when you compare it to the surrounding block work. Of course these days, being of a slightly more enquiring mind, I had to wonder why anyone would bother attaching metal plates to paving stones...

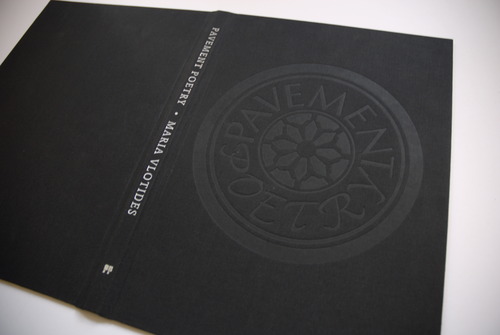

For a start the name 'ADAMANT' itself is very intriguing and throws up a couple of immediate associations

Firstly those of a particular generation might recall a time-travelling gentleman hero of the same name from the 60s

Whilst those of a slightly younger vintage might also remember another flamboyant performer

All very retro and refreshing for a slow afternoon but what, if anything, do these individuals have in common with a paving stone in Putney?

'ADAMANT' is as good a place to start as any. The Collins Dictionary defines it as

1. unshakable in purpose, determination, or opinion; unyieldingThe first two might fit our two video heros, but a legendary unbreakable semi-precious stone seems to fit nicely with the Putney paving slab. Trebles all round for the early advertising executive who came up with that name then!

2. a less common word for adamantine

1. any extremely hard or apparently unbreakable substance

2. (Myth & Legend / European Myth & Legend) a legendary stone said to be impenetrable, often identified with the diamond or loadstone

[Old English: from Latin adamant-, stem of adamas, from Greek; literal meaning perhaps: unconquerable, from a-1 + daman to tame, conquer]

Aberdeen is a useful clue as well and if there's one thing I know about Aberdeen it's the nickname of 'The Granite City' . A quick search came up with this result

The Adamant Stone & Paving Company of London and Aberdeen developed a mechanical method of producing very strong, very durable and very heavy paving slabs using granite chippings, portland cement and an incredibly powerful pneumatic press, the pressure from which was sufficient to bind the constituent parts together in one dense mass. No water required here and initially it took care of an exisiting industrial waste material, although I expect later on they were crushing granite to demand. It seems it was the development of a specific press that made the whole thing possible as this potted history makes clear:

As Portland cement became readily available, reliable and of sufficient quality, precasters started to benefit from the improved performance that the use of factory controlled conditions could provide, although very few recognised the full benefits at the time. With the Victorian passion for engineering and technological innovation, many advances in production techniques came about. Perhaps one of the least known of its time was the Fielding and Platt hydraulic press; the first hydraulic press in the UK, and possibly the world, which was was manufactured in 1890. Powered by water to rotate its sophisticated triple mould rotating table, the press developed 500 tons of force translated into 2 tons per square inch of product-pressing mechanism. The second press was manufactured three months later. It was transferred to the Adamant Stone and Paving Company of Aberdeen in 1897, where it then continued production for a further 73 years before its retirement – a truly magnificent performance.

Institute of Concrete Technology 2005/6

MILESTONES IN THE HISTORY OF CONCRETE TECHNOLOGY: A LOOK AT THE HISTORY OF PRECAST CONCRETE: Martin Clarke

That might explain the technological and historical background of the company, but it doesn't really explain why they might declare their patent in such a way on some of their paving slabs. I've no definitive answer for this, but I do have an idle speculation. When looking for details of the company there are frequent and tantalising references to a court case between the Adamant paving Company and the Municipal Corporation of Liverpool. Frustratingly I haven't yet found full details but it was basically a copywright issue and its cause might be guessed from this extract

"The total cost of the machinery as supplied and fixed by Messers Musker was £1275, the foundations and neccessary plant cost £225, exclusive of the clinker crusher which cost £45 making a total for the whole installation of £1545.The Removal and Disposal of Town Refuse

In connection with the above process The Adamant Stone Co. Ltd. in 1896 bought an action against the Liverpool Corporation..."

William Henry Maxwell, 1898

It seems this dispute was a fairly significant piece of case law and I would imagine it dealt with the method of production Liverpool employed to make its own paving slabs. Apparently not something Aberdeen Adamant were prepared to take lying down !

If Aberdeen Adamant had been succesful in their action, could the patent plaque on our paving slab have been a way of warning off any other possible infringements or even of establishing a prior claim to the process? I'm not sure but whether it's that or just a mundane case of basic advertising the plaque certainly adds a bit of interest to a paving slab - otherwise possibly the single most boring item on the street.